Dr. Iulian Gherasoiu, an associate professor at SUNY Polytechnic Institute, is part of a research team investigating how inexpensive catalyst materials behave inside next-generation hydrogen electrolyzers. Their recent study examines a nickel- and molybdenum-based catalyst designed for anion-exchange membrane (AEM) electrolysis, a method for splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen without relying on precious metals. The central question behind their work is whether lower-cost materials can maintain stable performance while reducing the economic barriers that continue to limit green hydrogen deployment.

Kumaran, Y., Gherasoiu, I., Cherniak, D. J., Kim, K.-Y., & Efstathiadis, H. (2026). Quantification of hydrogen and transition metals in ionomer-free MoNi4-MoO2 cathode catalyst layer for AEM electrolyzer. Electrochimica Acta, 546, 147829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2025.147829

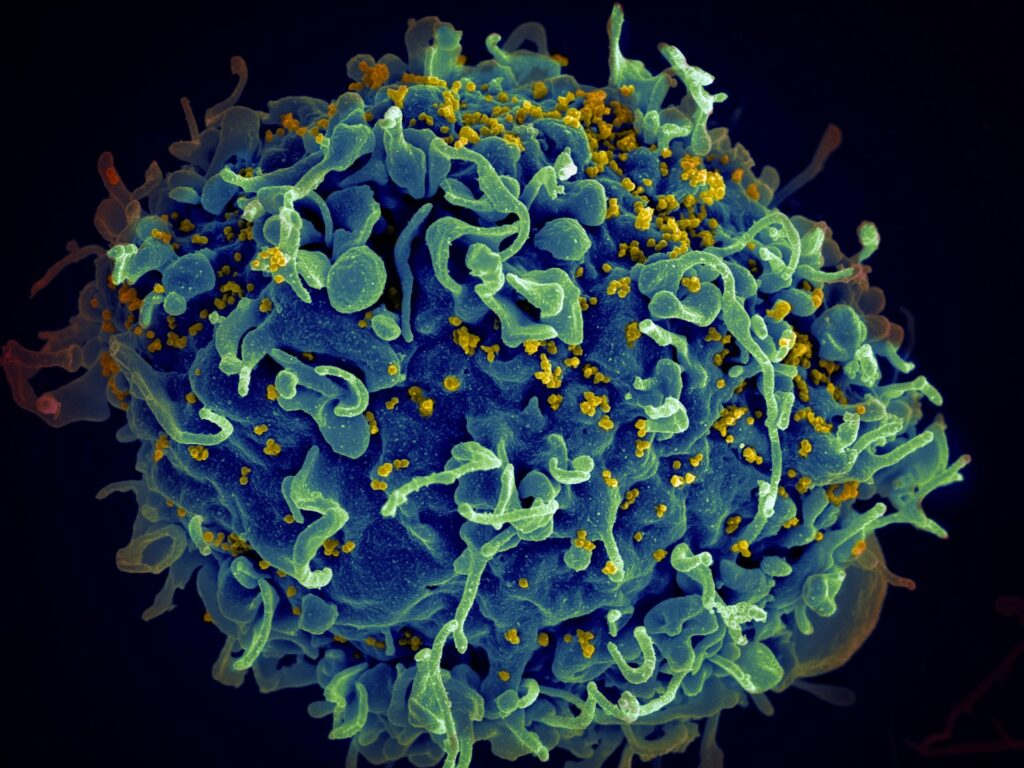

In this study, the researchers built a MoNi₄–MoO₂ catalyst and monitored how it performs under realistic electrolysis conditions. Unlike iridium or platinum, which are commonly used in commercial systems but are expensive and limited in supply, nickel and molybdenum are abundant and significantly cheaper. The team used a combination of imaging techniques and quantitative analysis to observe the material as it operated, focusing on how hydrogen and transition metals behave within the catalyst layer over time. Their findings show that the material performs effectively as a catalyst but undergoes gradual surface changes during use. These changes do not immediately hinder performance but may influence long-term durability, highlighting the need to understand degradation at the microscopic level before scaling up.

Their work sits within a broader movement across research groups working to reduce the cost of electrolyzers. Efforts at Northwestern University and the Toyota Research Institute have shown that large nanoparticle “megalibraries” can accelerate the discovery of alternative catalyst compositions, in some cases identifying promising candidates within hours. Another project at Hanyang University demonstrated that a boron-doped cobalt phosphide material can drive efficient water splitting without relying on rare metals, adding another option to a growing list of low-cost formulations. In parallel, several engineering teams continue to refine nickel-based catalysts, adjusting crystal structure, grain boundaries, and surface morphology to improve efficiency while keeping manufacturing practical.

What these studies collectively underscore is that the economic bottleneck in green hydrogen is tied closely to materials rather than the fundamental chemistry. Precious-metal catalysts work well but are not scalable to the global volumes that energy planners envision for hydrogen production. Even modest improvements in earth-abundant catalysts could substantially reduce system costs, especially if paired with progress in membrane durability, electrode design, and electrolyzer manufacturing. However, these advances must be matched by improvements in long-term stability. Many newly discovered catalysts show strong performance initially, but their behavior under fluctuating operating conditions—such as those created by renewable energy sources—remains a challenge.

Analyses from several energy-modeling groups indicate that without more robust low-cost catalysts, global hydrogen production may face material constraints, particularly for electrolyzer platforms still dependent on scarce metals. This makes the ability to monitor degradation, as demonstrated by Dr. Gherasoiu’s team, just as important as the discovery of new materials. Understanding how these catalysts evolve during operation offers researchers a clearer path toward engineering systems that are both efficient and durable.

While the field has not yet converged on a single solution, the pacing of current work suggests meaningful progress. Instead of relying solely on incremental improvements to existing precious-metal systems, researchers are now mapping out entirely new material families and testing how they behave under real electrochemical stress. If these efforts continue to align, the next generation of hydrogen electrolyzers could look fundamentally different from today’s designs—less dependent on rare metals, cheaper to manufacture, and better suited for large-scale, renewable-powered hydrogen production.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).