Researchers at the University of Sharjah, working with an international team of physicists and materials scientists, have reported unexpected electronic behavior that persists at room temperature under high pressure. Led by Mahmoud Abdel-Hafiez, associate professor of physics at the University of Sharjah, the study shows that certain collective electron patterns can strengthen rather than disappear when materials are compressed, challenging long-held assumptions in condensed matter physics and pointing toward new directions for electronic design.

Abdel-Hafiez, M., Sundaramoorthy, M., Jasim, N. M., Irshad, K. A., Kuo, C. N., Lue, C. S., Carstens, F. L., Bertrand, A., Mito, M., Klingeler, R., Borisov, V., Delin, A., Joseph, B., Eriksson, O., Arumugam, S., & Lingannan, G. (2025). Anomalous Pressure Dependence of the Charge Density Wave and Fermi Surface Reconstruction in <math display="inline"> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>BaFe</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mn>2</mn> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>Al</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mn>9</mn> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> </math>. Physical Review Letters, 135(23), 236502. https://doi.org/10.1103/dxzf-fx8k

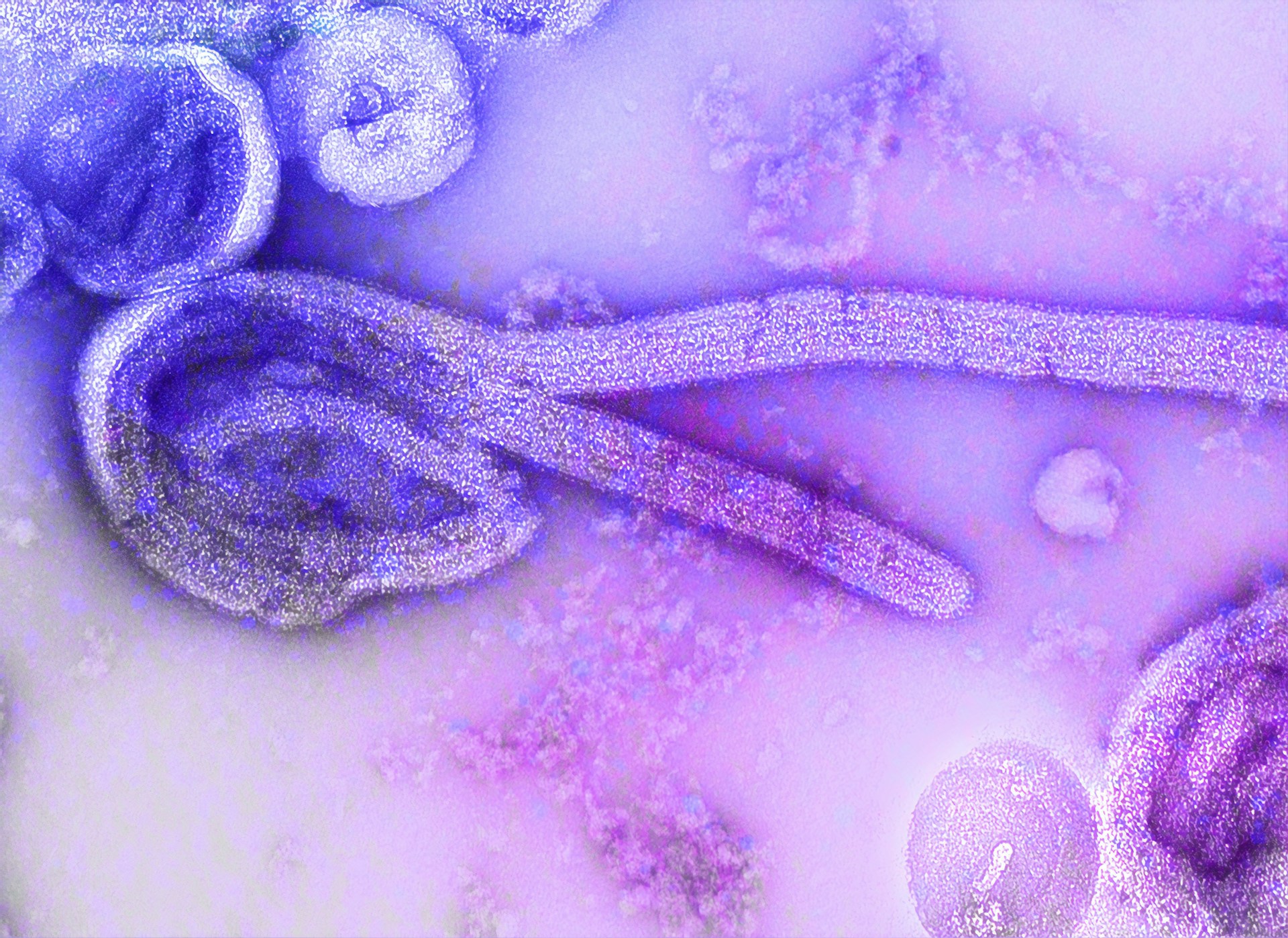

The work focuses on how electrons interact inside solids when subjected to extreme pressure. In many conventional materials, electrons behave largely as independent particles, and increasing pressure tends to disrupt ordered electronic states. However, in a specific iron-based compound examined in this study, the researchers observed the opposite trend. When pressure was applied, electrons began to act collectively, forming a charge-density wave that not only survived but remained stable up to room temperature.

Led by Mahmoud Abdel-Hafiez, associate professor of physics at the University of Sharjah stated,

“Another potential application lies in next-generation power systems. Understanding and controlling electron behavior could bring us closer to technologies like room-temperature superconductors, which could allow electricity to travel long distances without any energy loss. This would revolutionize power grids, lower costs, and support cleaner and more sustainable energy solutions.”

Charge-density waves are periodic modulations of electron density that can strongly influence how electrical current moves through a material. They are typically observed at low temperatures and often weaken or vanish as pressure increases. Using a combination of experimental measurements and density functional theory calculations, the team tracked how the electronic structure of the material evolved under compression. Their results showed a clear increase in the temperature at which the charge-density wave remained intact as pressure rose.

This behavior contrasts with what has been reported in many other layered and low-dimensional materials, where pressure suppresses similar electronic ordering. According to Abdel-Hafiez, forcing electrons closer together changes how they interact, revealing collective effects that are normally hidden under ambient conditions. The finding suggests that pressure can be used not only as a tuning parameter, but as a tool to stabilize electronic states that are otherwise inaccessible.

The study draws on contributions from researchers across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, including collaborators in Germany, Sweden, Japan, India, Italy, Egypt, Qatar, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates. Such breadth reflects the growing interest in correlated electron systems, where small changes in structure or external conditions can lead to large changes in material properties.

From an engineering perspective, the results are notable because electronic order that persists at room temperature is far easier to integrate into practical devices. While the experiments were carried out under high pressure, they provide proof that strong electron correlations do not inherently require low temperatures. This insight may guide future efforts to design materials that replicate similar behavior through chemical composition, strain, or layered architectures rather than pressure alone.

Independent experts note that the findings raise new questions about the mechanisms behind this unusually robust charge-density wave. Further studies using techniques such as angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, neutron scattering, and muon spin measurements are expected to help clarify why the electronic order strengthens instead of collapsing.

Although the work does not deliver a ready-to-use technology, it shifts the understanding of how electronic states respond to extreme conditions. By demonstrating that collective electron behavior can be stabilized at room temperature, the study provides a conceptual step toward materials that move electrical current more efficiently, generate less heat, and operate closer to everyday conditions.

For researchers working on next-generation electronics, energy transmission, and quantum materials, the results underline the value of exploring parameter spaces that were previously assumed to be unproductive. In this case, pressure revealed a regime where electrons behave in ways that defy standard expectations, offering new ground for both theoretical models and applied materials engineering.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).