A research team led by Professor Salvador Ventura at the Institute of Biotechnology and Biomedicine of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona has developed a new way to observe how disease-causing mutations alter the behavior of transthyretin, a protein involved in a group of progressive amyloid disorders. By applying mass spectrometry–based techniques that capture protein motion in solution, the study provides insights that could support the design of mutation-specific drugs for transthyretin amyloidosis.

Pinheiro, F., Kant, R., Chemuru, S., Varejão, N., Velázquez-Campoy, A., Reverter, D., Pallarès, I., Gross, M. L., & Ventura, S. (2026). Mass spectrometry footprinting reveals how kinetic stabilizers counteract transthyretin dynamics altered by pathogenic mutations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 123(1). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2519908122

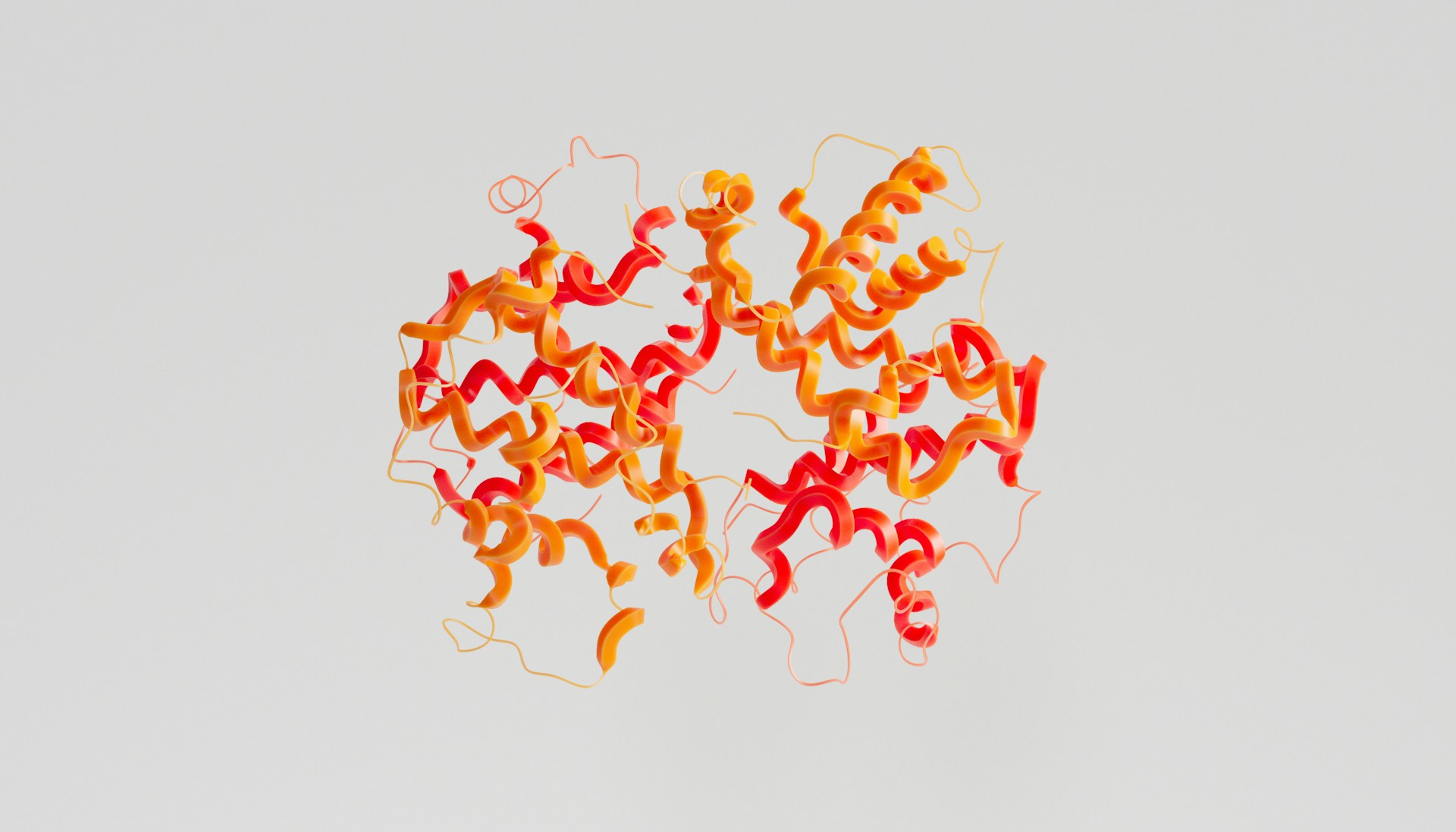

Transthyretin, commonly referred to as TTR, is a transport protein produced primarily in the liver, with additional synthesis in the brain. Under normal conditions, it circulates as a stable tetramer. Certain inherited mutations, as well as age-related destabilization, can cause the tetramer to dissociate into monomers that misfold and aggregate. These aggregates accumulate as amyloid fibrils in organs such as the heart and peripheral nerves, giving rise to transthyretin amyloidosis, or ATTR, a set of disorders that progress over time and can be fatal if untreated.

Professor Salvador Ventura at the Institute of Biotechnology and Biomedicine of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona stated,

“By applying mass spectrometry (MS) combined with two biochemical techniques, such as hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX) and fast photochemical oxidation of proteins (FPOP), we were able to observe the changes in conformation induced by both mutations and ligand binding, which are invisible to X-ray crystallography.”

Over the past decades, structural biology has produced hundreds of high-resolution TTR crystal structures. While these structures have been essential for understanding the protein’s architecture, they represent static conformations. They do not adequately capture how mutations alter the stability of the tetramer in solution or how the protein fluctuates between folded and aggregation-prone states. This limitation has practical consequences, particularly for drug development, where existing stabilizing compounds show broad activity but are not optimized for specific disease-associated variants.

To address this gap, the research team combined mass spectrometry with hydrogen–deuterium exchange and fast photochemical oxidation of proteins. These techniques measure how readily different regions of a protein interact with the surrounding solvent, providing indirect but quantitative information about flexibility, exposure, and conformational change. In contrast to crystallography, which freezes proteins into a single state, these approaches capture an ensemble of conformations as the protein behaves in solution.

Using this methodology, the researchers analyzed several pathogenic TTR variants and compared them with the wild-type protein. The data revealed mutation-specific destabilization mechanisms that had not been detected previously. Certain regions of the protein showed increased flexibility or exposure, suggesting early steps toward tetramer dissociation and aggregation. Importantly, the study also examined how small-molecule stabilizers interact with both wild-type and mutant TTR. The results showed that ligand binding can partially counteract mutation-induced destabilization, but the extent and location of stabilization differ depending on the variant.

These findings have implications for the design of next-generation therapies. Current drugs for ATTR focus on slowing tetramer dissociation, but they are largely designed using static structural models. By incorporating dynamic information from mass spectrometry, drug developers may be able to design compounds that better match the mechanical and conformational behavior of specific mutations. This approach could improve therapeutic response and reduce variability between patients with different genetic backgrounds.

From an engineering perspective, the work highlights the value of integrating dynamic structural tools into biomedical research pipelines. Techniques such as hydrogen–deuterium exchange and oxidative footprinting provide system-level information that complements atomic-resolution structures. Similar approaches are increasingly relevant in protein engineering, where understanding flexibility, stability, and conformational transitions is critical for designing functional molecules.

The study demonstrates that capturing protein dynamics is not simply a refinement of existing structural methods, but a necessary step for understanding diseases driven by subtle stability changes. For transthyretin amyloidosis, this shift from static images to dynamic measurements may enable more precise therapeutic strategies and more informative diagnostic tools in the future.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).