Researchers at the University of York have demonstrated how automation and chemistry can be combined to accelerate the search for new antibiotics, addressing a growing concern over drug-resistant infections. Led by Dr. Angelo Frei in the Department of Chemistry, the team developed a robotic synthesis platform capable of producing and testing hundreds of metal-based compounds in a matter of days, rather than months.

Husbands, D. R., Özsan, Ç., Welsh, A., Gammons, R. J., & Frei, A. (2025). High-throughput triazole-based combinatorial click chemistry for the synthesis and identification of functional metal complexes. Nature Communications, 16(1), 11195. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67341-z

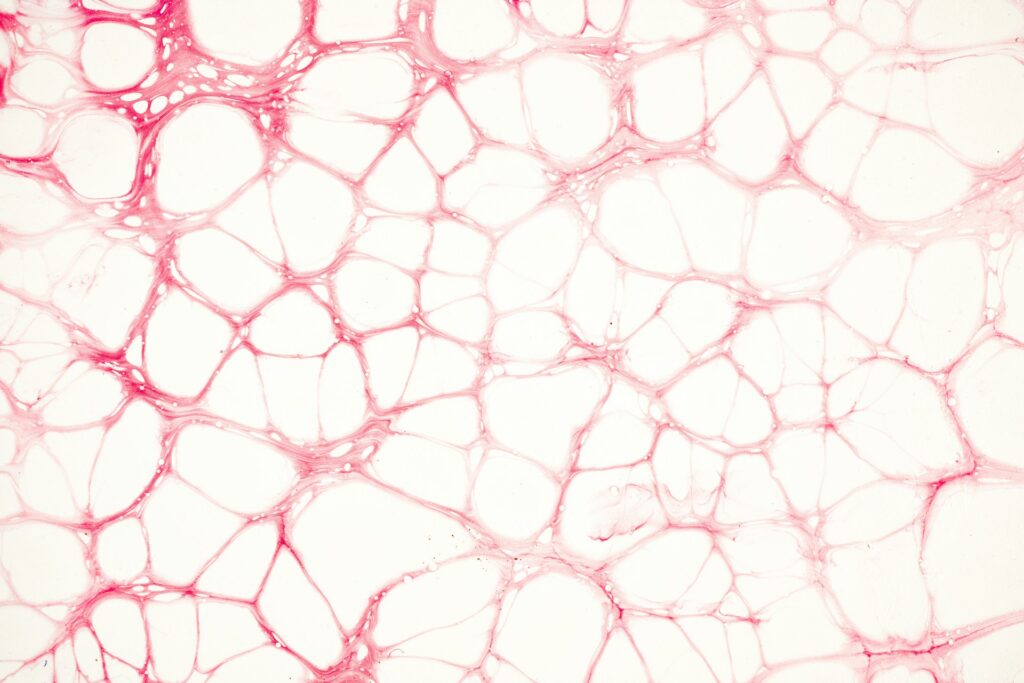

The study builds on the idea that metal complexes represent a largely underexplored area in antibiotic development. Most antibiotics in current clinical use are organic, carbon-based molecules with relatively flat structures. In contrast, metal complexes are three-dimensional and can interact with bacterial cells in ways that differ from conventional drugs. This structural diversity offers a potential route around resistance mechanisms that have rendered many existing antibiotics ineffective.

Dr. Angelo Frei in the Department of Chemistry University of York stated,

“The iridium compound we discovered is exciting, but the real breakthrough is the speed at which we found it. This approach could be the key to avoiding a future where routine infections become fatal again.”

Using an automated system combined with click chemistry, the researchers rapidly assembled a large library of compounds. The platform mixed nearly 200 different ligands with five metal centers, producing more than 700 distinct metal complexes in under a week. Click chemistry was key to this process, allowing molecular components to be joined efficiently and reliably, which made the reactions well suited to automation.

Once synthesized, the compounds were screened for antibacterial activity and for toxicity toward human cells. This parallel testing step was critical, as many potential antibiotics fail because they harm healthy cells. From the initial library, six compounds showed promising antibacterial properties while remaining relatively non-toxic in early tests.

One iridium-based complex stood out in particular. It was effective against bacteria related to clinically significant drug-resistant strains, while maintaining low toxicity to human cells. This balance suggests a favorable therapeutic window and makes the compound a strong candidate for further investigation. While it remains at an early stage, the result highlights the potential of metal complexes as viable antibiotic leads.

Beyond the identification of a single candidate, the researchers emphasize the importance of the methodology itself. Antibiotic discovery has slowed in recent decades due to high costs and low commercial incentives, leading many pharmaceutical companies to scale back their efforts. By automating synthesis and screening, the York team demonstrated a way to explore large areas of chemical space quickly and systematically, reducing time and labor barriers.

The work also challenges long-standing assumptions about metal-based drugs. Metals are often associated with toxicity, but recent data from broader antimicrobial screening initiatives suggest that metal complexes can have higher success rates against bacteria without necessarily increasing harm to human cells. The York study adds further evidence that these compounds merit closer attention.

Looking ahead, the team plans to study how the iridium compound interacts with bacterial cells at a molecular level and to expand the robotic platform to include additional metals and ligand families. The same approach could also be adapted for applications beyond medicine, such as the discovery of new catalysts for chemical manufacturing.

For engineers and researchers working at the intersection of chemistry, automation, and biomedical science, the study illustrates how robotic systems can reshape traditional discovery pipelines. Rather than replacing human insight, automation in this case acts as a force multiplier, enabling researchers to test ideas at a scale and speed that would otherwise be impractical.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).