Chemists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, led by Professor Mei Hong, have reported a detailed structural analysis of a long-overlooked region of the Tau protein, a molecule strongly associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Using advanced nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, the team has mapped the so-called “fuzzy coat” that surrounds Tau fibrils, offering new insight into how these proteins interact, aggregate, and potentially resist therapeutic intervention.

Zhang, J. Y., Dregni, A. J., & Hong, M. (2026). Heterogeneous Dynamics of the Fuzzy Coat of Full-Length Phospho-Mimetic Tau Fibrils. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 148(1), 1623–1637. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c18540

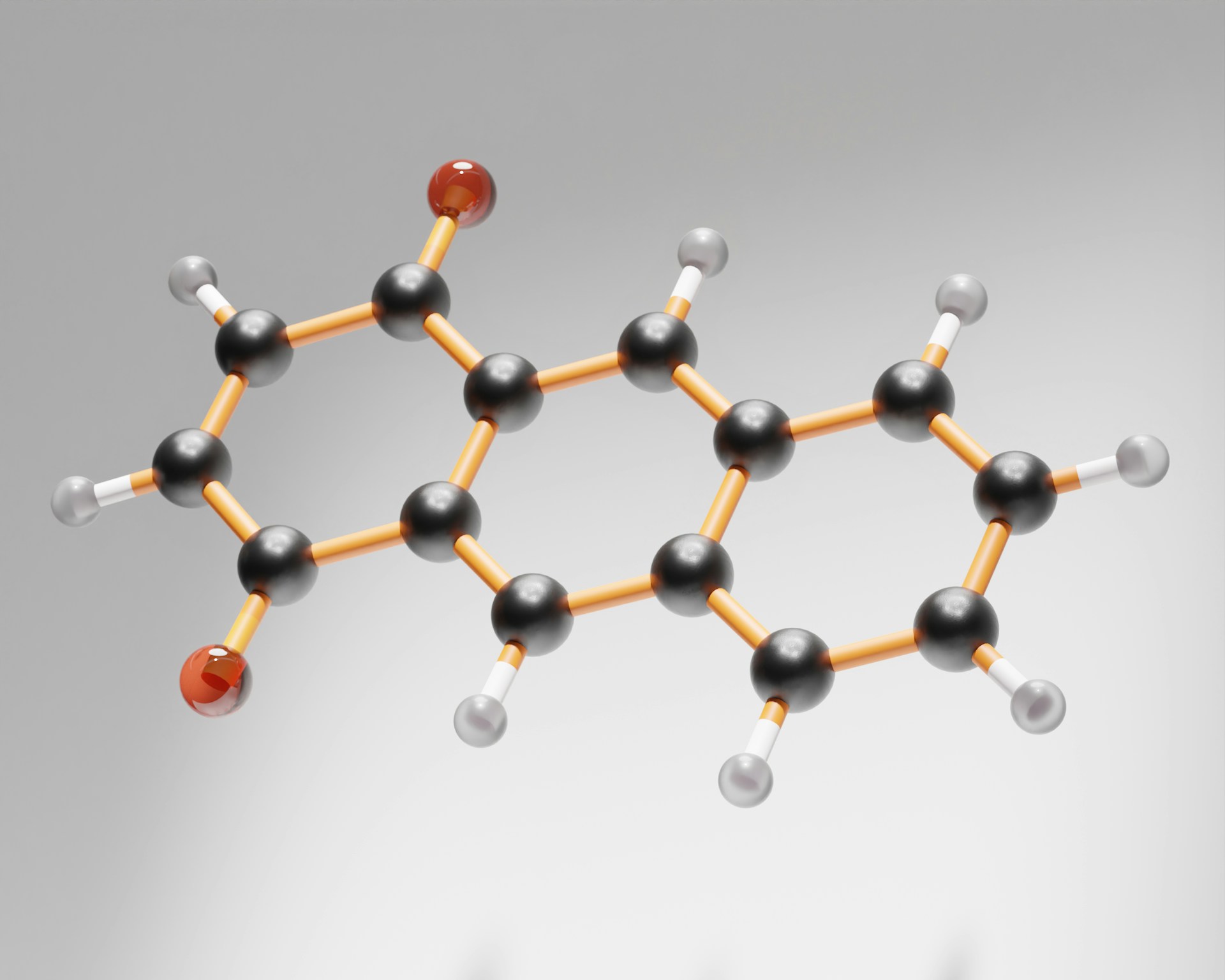

Tau proteins play a functional role in healthy neurons by stabilizing microtubules, but under pathological conditions they misfold and assemble into fibrils that accumulate in the brain. These fibrils are known to contain a tightly ordered inner core, but most of the protein mass exists in flexible, disordered segments that extend outward. This outer region, referred to as the fuzzy coat, accounts for roughly 80 percent of the protein and has historically been difficult to characterize due to its dynamic nature.

Professor Mei Hong from Massachusetts Institute of Technology stated,

“We have now developed an NMR-based technology to examine the fuzzy coat of a full-length Tau fibril, allowing us to capture both the dynamic regions and the rigid core.”

Traditional structural tools such as X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have been effective at resolving rigid protein structures but are poorly suited to capturing highly mobile regions. As a result, most prior studies focused almost exclusively on the Tau core. The MIT team instead adapted solid-state NMR techniques to probe both rigid and mobile portions of full-length Tau fibrils in a single framework.

In their experiments, the researchers selectively magnetized protons in rigid amino acids and measured how magnetization transferred over time to more mobile segments. By tracking these interactions, they were able to estimate spatial proximity between the core and surrounding regions while also measuring the degree of motion across different parts of the protein. Complementary NMR measurements allowed them to classify segments of the fuzzy coat based on their mobility.

The results suggest that Tau fibrils adopt a layered architecture, with the rigid beta-sheet core wrapped by multiple shells of increasingly dynamic protein regions. The researchers described the overall structure as resembling a burrito, where the most flexible segments form the outermost layer. Notably, the most mobile regions were found to be rich in proline residues, amino acids previously thought to be partially constrained due to their proximity to the core.

Instead, the data indicate that these proline-rich segments remain highly dynamic, likely due to electrostatic repulsion between positively charged regions of the fuzzy coat and the similarly charged core. This behavior helps explain how the fuzzy coat maintains separation from the core while still influencing how Tau fibrils interact with surrounding molecules.

These structural features have implications for understanding how Tau aggregation spreads in the brain. Current models suggest that misfolded Tau proteins act as templates, inducing normal Tau to adopt the same abnormal structure. The new findings indicate that because the fuzzy coat envelops the sides of the fibril, incoming Tau proteins are more likely to attach at the ends, promoting elongation rather than lateral growth.

From an engineering and drug-design perspective, the work highlights a practical challenge. Any small-molecule therapy aimed at breaking apart Tau fibrils must first navigate the dynamic fuzzy coat before reaching the rigid core. By quantifying the structure and motion of this outer layer, the study provides a framework for designing compounds capable of penetrating or interacting with it effectively.

The research team plans to extend this approach by studying how pathological Tau extracted from Alzheimer’s patients influences fibril formation in healthy Tau proteins. Such experiments could help clarify how disease-specific structures emerge and propagate, potentially guiding the development of more targeted interventions.

The study was led by MIT graduate researcher Jia Yi Zhang, with contributions from former MIT postdoctoral researcher Aurelio Dregni, and was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. While the findings do not offer an immediate therapeutic solution, they represent a methodological advance in studying disordered protein systems that are central to many neurological diseases.

For engineers and materials scientists, the work underscores how tools traditionally used in solid-state physics and chemistry can be adapted to resolve biological problems where disorder, motion, and heterogeneity are not obstacles, but defining features of the system itself.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).