Chibueze Amanchukwu, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, has led a study that turns an unwanted feature of battery chemistry into a potential tool for environmental cleanup. DrawingToggle shift on observations of how certain battery electrolytes degrade under extreme electrochemical conditions, Amanchukwu and his collaborators have developed a method to intentionally break down per and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly known as PFAS.

Sarkar, B., Kumawat, R. L., Ma, P., Wang, K.-H., Mohebi, M., Schatz, G. C., & Amanchukwu, C. v. (2026). Lithium metal-mediated electrochemical reduction of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances. Nature Chemistry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-02057-7

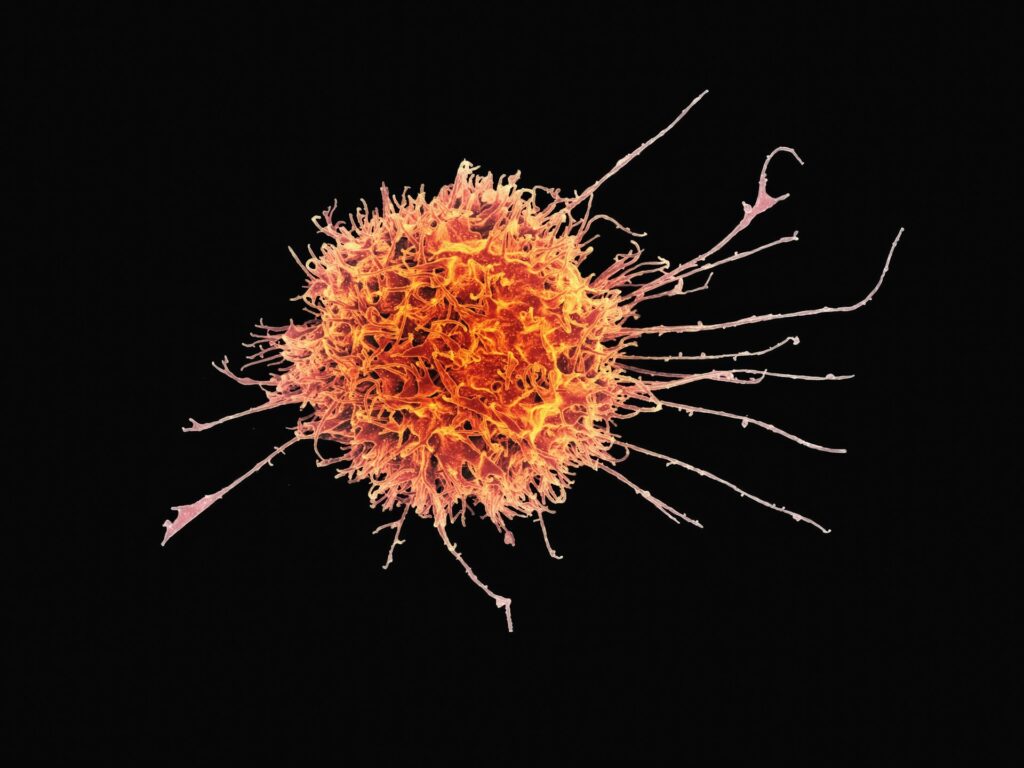

PFAS are often described as “forever chemicals” because their carbon fluorine bonds are among the strongest in organic chemistry. These bonds give PFAS their useful properties, such as resistance to heat, water, and oil, but also make them highly persistent in the environment. Conventional treatment approaches tend to rely on oxidation, high temperatures, or energy intensive processes, and many methods only shorten PFAS chains rather than fully destroying them.

Chibueze Amanchukwu, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago stated,

“The intention is to try to get scientists to interact with each other who might not normally interact. This has been an exciting outcome associated with the AMEWS Center.”

The approach developed by Amanchukwu’s team takes a different direction. Instead of oxidizing PFAS, the researchers focused on reduction by adding electrons until the carbon fluorine bonds become unstable. This strategy emerged from battery research, where fluorinated compounds are known to degrade under highly reducing conditions inside non aqueous electrolytes. What is usually considered a failure in battery performance became the basis for a controlled destruction pathway.

In the reported experiments, the researchers used a non aqueous electrochemical system in which lithium metal is generated on a copper electrode. When PFAS molecules are introduced into this environment, the reducing conditions preferentially attack the fluorinated compounds rather than the solvent. In tests using perfluorooctanoic acid, a well studied long chain PFAS, the method achieved close to complete breakdown, with most of the fluorine converted into inorganic fluoride rather than smaller organic fragments.

This distinction is important because partial degradation can create shorter chain PFAS that are more mobile in water and harder to capture with existing filtration technologies. By pushing the reaction toward near complete defluorination, the new method avoids generating these secondary contaminants and instead mineralizes the fluorine into a more stable form.

The team extended the approach beyond a single compound, testing it on a broader set of PFAS molecules. A majority of the compounds examined showed substantial degradation, indicating that the underlying chemistry may apply to a wider portion of the PFAS family. External researchers have described the work as a conceptual advance, particularly because it relies on reductive electrochemistry rather than the oxidative pathways more commonly explored in this area.

From an engineering perspective, the method highlights how insights from one field can inform solutions in another. Electrochemical systems are inherently modular, and in principle could be powered by renewable electricity and deployed close to contaminated sites. While the current experiments were carried out in controlled laboratory conditions, the researchers emphasize that scaling and system design remain key challenges before practical deployment.

The study also reflects a broader shift in how environmental problems are approached, with increasing attention paid to destroying pollutants rather than simply isolating them. By repurposing knowledge from battery degradation, Amanchukwu and his colleagues have shown that even well known failure mechanisms can become useful tools when viewed through a different lens.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).