Cancer therapies increasingly aim to act with greater precision, intervening at the level of specific proteins rather than broadly affecting entire cells. At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, a research team led by Sankaran “Thai” Thayumanavan has developed two complementary platform technologies that take this idea a step further by directly reshaping the protein landscape on the surface of living cells. The work combines chemistry, biomedical engineering, and cell biology to either remove malfunctioning membrane proteins or replace them with functional ones, offering a flexible framework that could extend beyond cancer to other diseases driven by protein dysfunction.

Lu, R. H.-H., Krishna, J., Alp, Y., & Thayumanavan, S. (2026). Polymeric Lysosome-Targeting Chimeras (PolyTACs): Extracellular Targeted Protein Degradation without Co-Opting Lysosome-Targeting Receptors. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 148(1), 1259–1270. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c17519

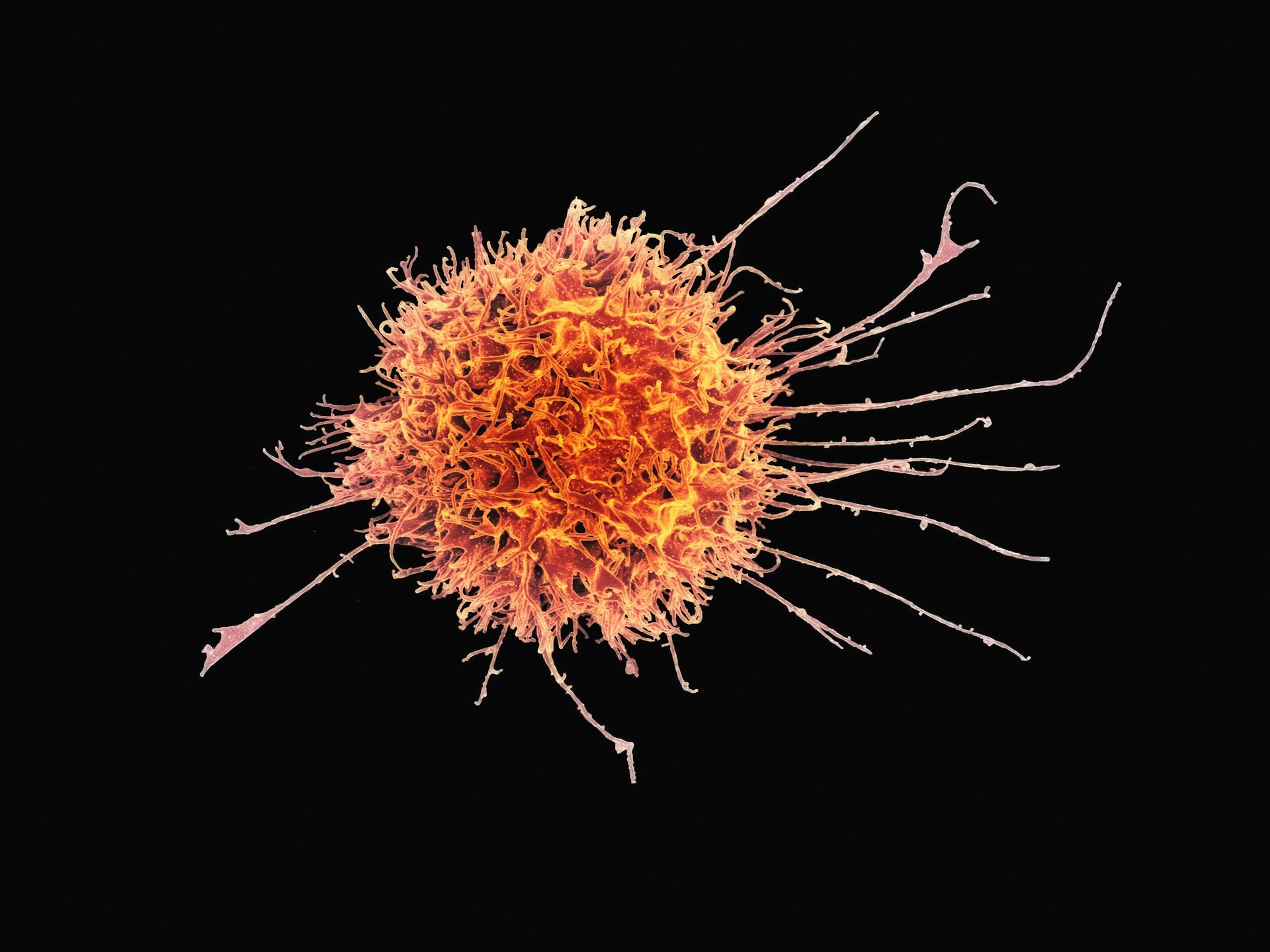

Cell membranes are often described as protective barriers, but in practice they are active interfaces crowded with proteins that regulate how cells communicate with their environment. Many cancers exploit these surface proteins, using altered or overexpressed versions to trigger uncontrolled growth or to evade immune detection. While only a fraction of the body’s proteins reside on the cell membrane, they account for a large share of existing drug targets, reflecting their importance and accessibility.

University of Massachusetts Amherst, a research team led by Sankaran “Thai” Thayumanavan stated,

“The platform that we built is called an ‘artificial cell-derived vesicle,’ or ACDV, and it allows us to directly fix what’s wrong with the cell by adding proteins, in real time, using a flexible process.”

One branch of the UMass Amherst work focuses on selectively removing harmful membrane proteins without relying on traditional biochemical tagging pathways. The team developed what they call polymeric lysosome targeting chimeras, or PolyTACs. These constructs pair a targeting antibody with a polymer that exerts a localized physical force on the cell membrane. When the antibody binds to a specific protein, the attached polymer creates a small indentation at that precise location. This mechanical deformation triggers the cell’s own internalization machinery, pulling the targeted protein into the cell and routing it to the lysosome, where it is broken down.

This mechanism differs from existing protein degradation strategies that depend on hijacking cellular receptors or signaling cascades. Instead, it exploits a physical response of the membrane itself. Graduate researchers Ryan Lu and Jithu Krishna, who led much of the experimental work, showed that this approach can guide the cell to dispose of a chosen protein while leaving surrounding proteins largely unaffected. By focusing on one defined target at a time, the method offers a level of specificity that is difficult to achieve with small molecules or conventional antibodies alone.

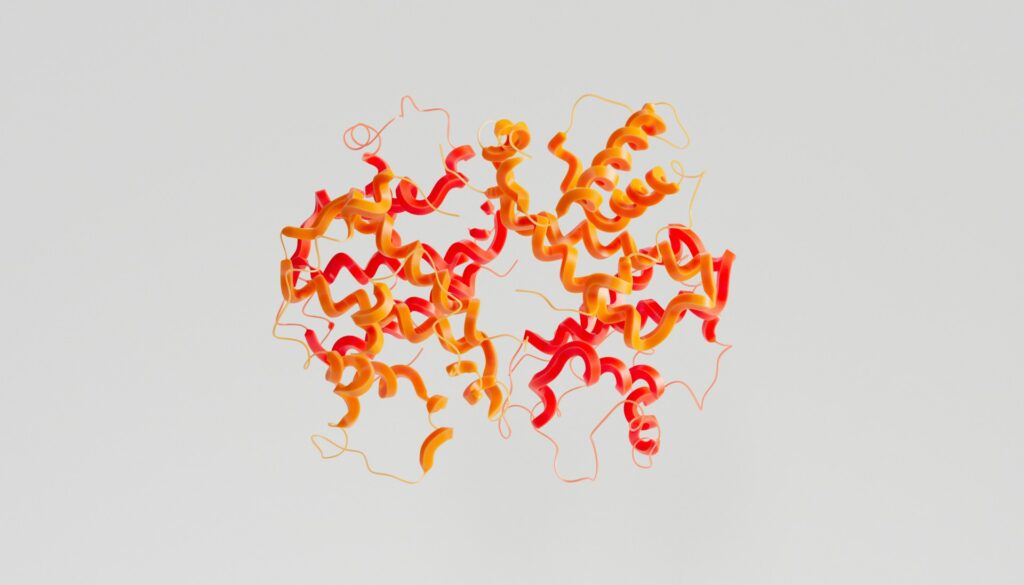

A second platform developed by the group addresses the opposite problem. Rather than destroying defective proteins, it aims to restore healthy function by adding new ones. This system uses artificial cell derived vesicles, or ACDVs, which can fuse with a cell membrane and deliver fully functional proteins directly to the surface. Once incorporated, these proteins become part of the membrane’s working machinery.

Researchers Shuai Gong and Jingyi Qiu demonstrated that multiple proteins could be installed in this way, effectively reprogramming how a cell interacts with its surroundings. In cancer models, this opens the possibility of removing the molecular “mask” that allows malignant cells to avoid immune recognition or of reinstating signals that suppress abnormal growth. Because the proteins are delivered intact, the approach avoids the need to correct or modify damaged versions already present on the cell.

Both strategies were reported in separate studies published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, reflecting a shared emphasis on modular design. Rather than developing a single therapy for a single disease, the team has focused on building platforms that can be adapted by swapping antibodies, polymers, or protein cargos. This flexibility is particularly relevant as cancer treatment moves toward personalized approaches, where therapies are tailored to the specific molecular profile of a patient’s tumor.

From an engineering standpoint, the work highlights how physical principles can be integrated into biological interventions. The PolyTAC system relies as much on mechanical interaction with the membrane as on molecular recognition, while the ACDV approach draws on concepts from materials science and membrane fusion. Together, they illustrate a broader trend in biomedical engineering toward tools that work with cellular processes rather than attempting to override them.

While the current studies were carried out in controlled laboratory settings, the researchers emphasize that further work is needed to evaluate safety, delivery, and effectiveness in more complex biological systems. Even so, the results suggest that directly editing the protein composition of cell surfaces could become a practical strategy in the future. By treating the cell membrane as an adjustable interface rather than a fixed boundary, these platform technologies offer a new way to think about how diseases driven by protein dysfunction might be addressed.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).