Researchers at the University of Groningen are reporting new insights into how metamaterials behave when scaled up, findings that could influence the design of medical implants, robotic grippers and impact absorbing structures. The work, led by Ph.D. researcher H.C.V.M. Shyam Veluvali and Professor Anastasiia Krushynska, was carried out in collaboration with University Medical Center Groningen and Karlstad University and published in Small Structures.

Veluvali, H. C. V. M. S., Beniwal, S., Nika, G., Kraeima, J., Onck, P. R., & Krushynska, A. O. (2026). When Scale Matters: Size‐Dependent Mechanics of Architected Lattices for Implants and Beyond. Small Structures, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/sstr.202500434

Metamaterials differ from conventional materials in that their properties arise primarily from geometry rather than composition. They are typically built from repeating units known as unit cells, arranged in regular lattices. Much of the previous research in this field has examined the mechanical response of a single unit cell or assumed that large assemblies behave in a straightforward, predictable way. The Groningen team questioned that assumption.

Ph.D. researcher H.C.V.M. Shyam Veluvali and Professor Anastasiia Krushynska from University of Groningen stated,

“Our insights help to design safer, longer-lasting structures for various applications by choosing the right block size and arrangement.”

Using additively manufactured polymer lattices, the researchers systematically varied the size of unit cells and the total number of cells within a structure. Their experiments show that mechanical behavior, including elasticity and stiffness, depends not only on the geometry of individual cells but also on how many are connected and how they are arranged. In smaller assemblies, edge effects and local constraints play a larger role, leading to measurable deviations from the response predicted by idealized models. As the number of unit cells increases, the overall behavior becomes more uniform and easier to predict.

The team also examined how different types of loading influence the same lattice. While earlier studies often focused on a single loading mode, such as compression, this work compared responses under stretching, shear and torsion. The results indicate that identical metamaterial architectures can exhibit different scale dependent behavior depending on the applied force. In practical terms, a design optimized for compressive loads may not perform as expected under twisting or shear.

These findings are particularly relevant for biomedical engineering. Conventional bone implants are commonly made from titanium alloys, which are significantly stiffer than natural bone. Because the implant carries most of the mechanical load, the surrounding bone can experience reduced stress and gradually weaken. The researchers propose that architected metamaterial implants could be tuned to better match the stiffness of bone, allowing load sharing and potentially preserving bone strength over time. However, the study suggests that accurate predictions require careful consideration of lattice size and configuration rather than relying solely on unit cell properties.

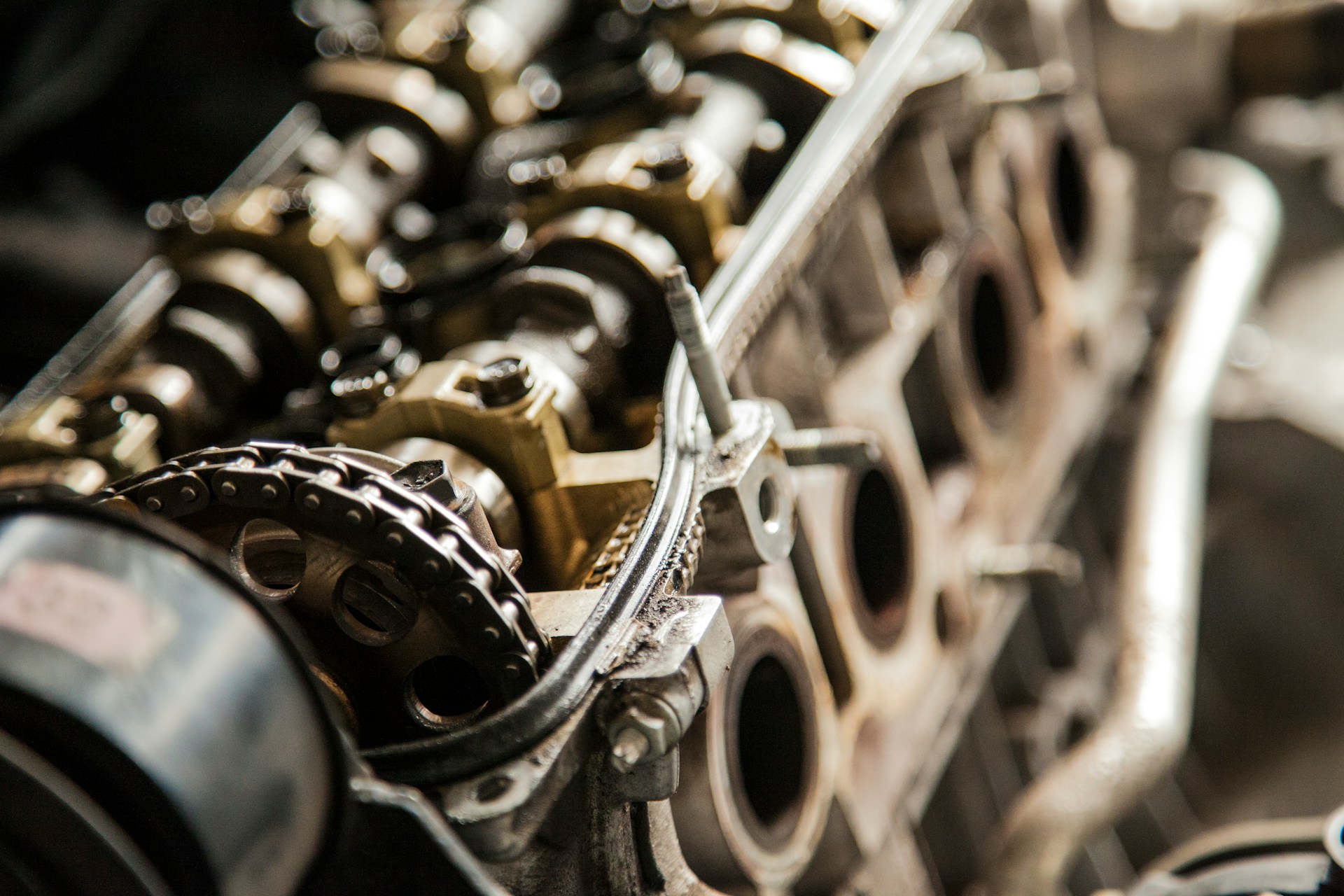

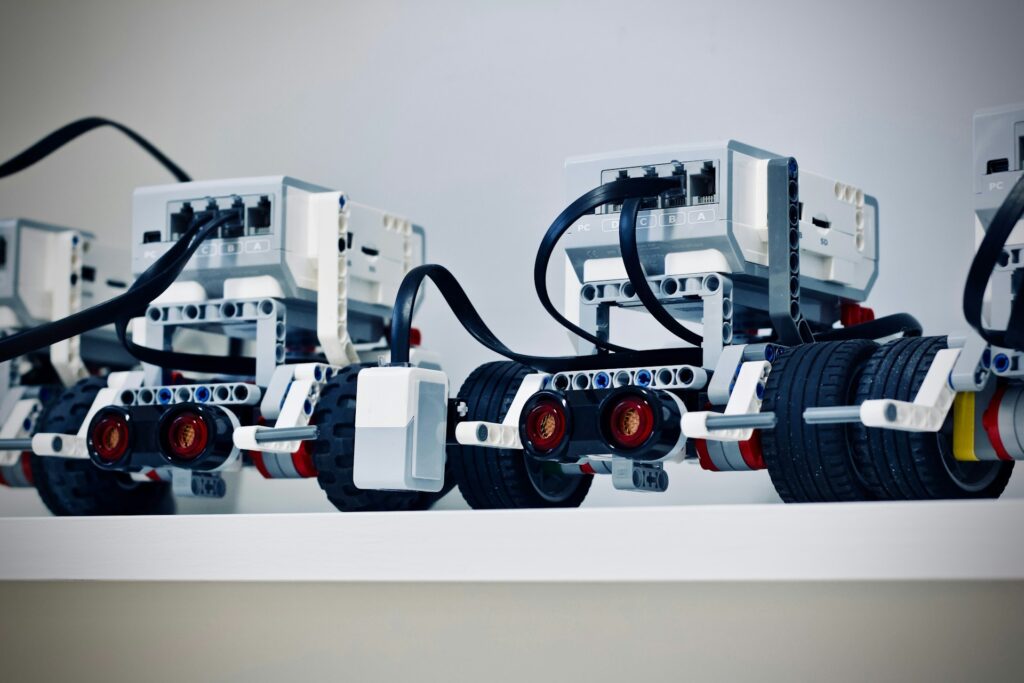

Beyond implants, the work has implications for robotic systems and impact mitigation. Robotic hands, for example, require gripper materials that balance compliance and strength. Similarly, energy absorbing components such as automotive bumpers depend on predictable deformation under dynamic loads. By understanding how lattice scale influences stiffness and failure modes, engineers can design structures that meet specific mechanical targets more reliably.

The study contributes to a broader effort in architected materials research to bridge the gap between laboratory scale samples and real world components. Additive manufacturing has made it feasible to produce complex lattices with controlled geometry, but translating theoretical models into practical designs requires attention to boundary conditions, loading modes and structural scale.

In this context, the Groningen team’s findings highlight that scale is not a secondary parameter. The number of repeating cells and their arrangement can materially alter mechanical response, especially in smaller devices where edge effects are significant. As metamaterials move from conceptual demonstrations to functional implants and engineered components, such insights will be central to ensuring predictable and durable performance.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).