Jure Zupan, a professor of physics at the University of Cincinnati, has led a new theoretical study examining whether nuclear fusion reactors could be used to produce particles linked to dark matter. Working with collaborators from Fermilab, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Zupan and his colleagues outline how the extreme conditions inside fusion systems may provide an additional way to investigate one of the most persistent questions in modern physics.

Baruch, C., Fitzpatrick, P. J., Menzo, T., Soreq, Y., Trifinopoulos, S., & Zupan, J. (2025). Searching for exotic scalars at fusion reactors. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2025(10), 215. https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP10(2025)215

Dark matter is believed to account for most of the matter in the universe, yet it has never been directly observed. Its presence is inferred from gravitational effects that influence the motion of galaxies and large scale cosmic structures. Understanding what dark matter is made of remains central to explaining how the universe evolved following the Big Bang.

Among the leading candidates for dark matter are axions, hypothetical particles originally proposed to resolve inconsistencies in the theory of strong nuclear interactions. Axions are predicted to be very light and to interact only weakly with ordinary matter, which has made them difficult to detect using conventional experimental methods. As a result, researchers have explored a wide range of detection strategies, from deep underground laboratories to observations of astrophysical sources.

Jure Zupan, a professor of physics at the University of Cincinnati stated,

“The sun is a huge object producing a lot of power. The chance of having new particles produced from the sun that would stream to Earth is larger than having them produced in fusion reactors using the same processes as in the Sun. However, one can still produce them in reactors using a different set of processes.”

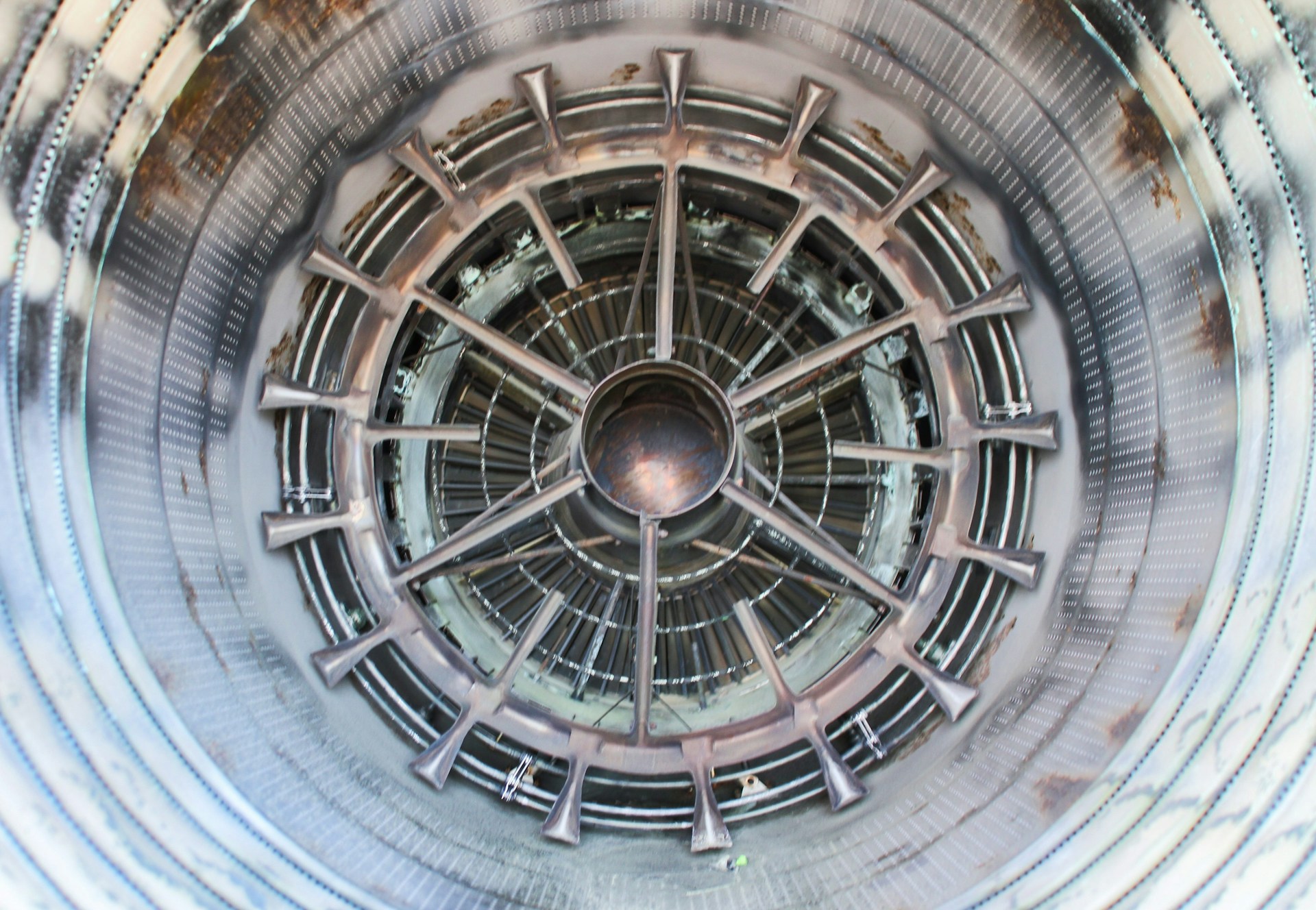

The new study explores whether fusion reactors could act as controlled sources of axions or axion like particles. Fusion systems that rely on deuterium and tritium reactions generate large numbers of high energy neutrons. These neutrons interact with surrounding materials in reactor vessels, producing secondary nuclear reactions that can give rise to new particles not typically produced in simpler experimental setups.

In addition to direct nuclear interactions, the researchers examined how neutrons slow down as they scatter through reactor components. During this process, energy is released in the form of radiation, a phenomenon known in nuclear physics as braking radiation. Under certain theoretical conditions, this radiation could also lead to the production of axion like particles.

A key advantage of fusion reactors, according to the authors, is the ability to control and monitor operating conditions. Unlike astrophysical sources such as the Sun, where particle production occurs across vast and poorly constrained environments, fusion reactors allow researchers to correlate particle generation with known inputs such as fuel composition and power output. This controlled setting could help reduce uncertainties in future experiments.

The study revisits ideas that have circulated informally among physicists for years, including those that have appeared in popular culture. Earlier attempts to evaluate axion production in fusion environments focused primarily on processes analogous to those occurring in stars and concluded that detection would be unlikely. The new work suggests that alternative nuclear processes in reactors may change that assessment.

The authors stress that their findings remain theoretical. Detecting axions would require highly sensitive instruments capable of operating near fusion facilities, where background radiation levels are high. Designing such detectors and distinguishing potential signals from noise represent significant engineering and experimental challenges.

Despite these obstacles, the research highlights how fusion reactors may offer scientific value beyond energy generation. As fusion technology advances, facilities could serve as platforms for studying fundamental physics alongside their primary role in producing low carbon energy.

By extending the use of fusion systems into particle physics research, the study illustrates how interdisciplinary approaches can open new directions in long standing scientific problems. While dark matter remains undetected, the work provides a framework for exploring how engineered environments might contribute to answering questions traditionally addressed through astrophysical observation alone.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).