For nearly 30 years, researchers have known that certain compounds found in rye pollen can slow tumor growth in animal models. What has been missing is a clear understanding of what those molecules actually look like. That gap has now been closed by a chemistry team at Northwestern University, led by Karl A. Scheidt, providing a structural foundation that could allow this long-standing observation to be explored in a more systematic and engineering-driven way.

Nam, Y., Tam, A. T., Reynolds, T. E., Rojas, D. N., Brekan, J. A., Sil, S., & Scheidt, K. A. (2026). Synthesis and Structural Confirmation of Secalosides A and B. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 148(1), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c18864

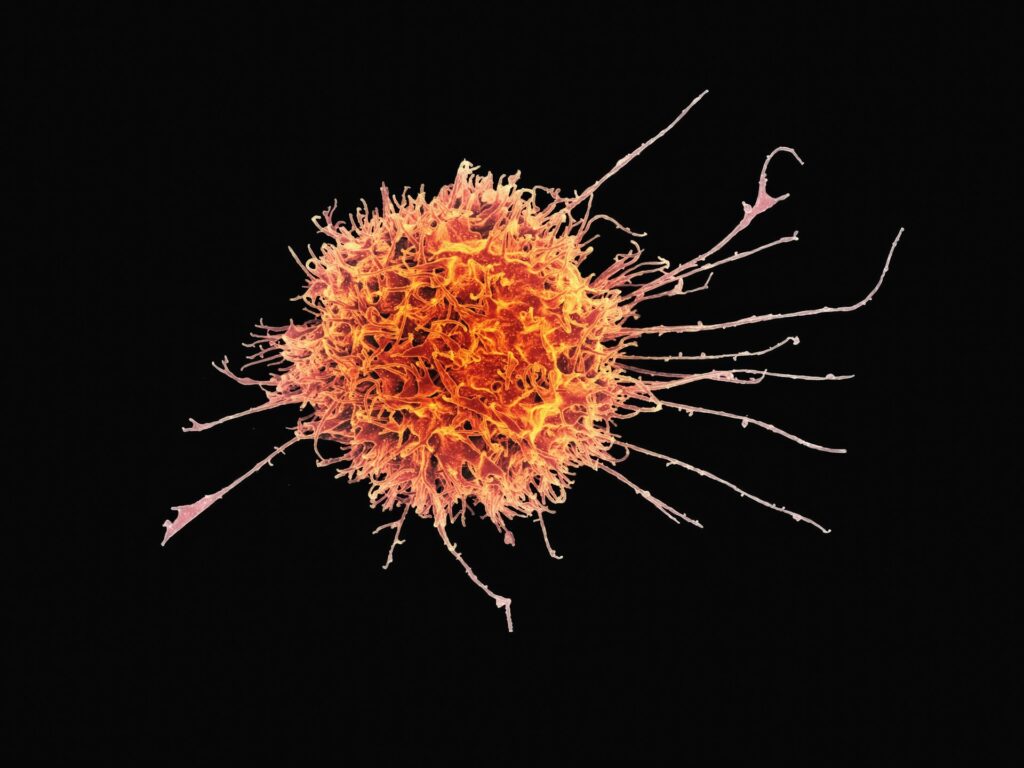

The study focuses on two molecules known as secalosides A and B. These compounds were first isolated decades ago and shown to have anti-tumor activity through mechanisms that appeared non-toxic and linked to immune response. Despite repeated efforts, their precise three-dimensional structures remained unresolved, limiting progress. Without a reliable molecular blueprint, it was impossible to determine which parts of the compounds were biologically active or how they interacted with cells.

Northwestern University, led by Karl A. Scheidt stated,

“We’ve demonstrated we can make the core of this natural product. Now, we’re trying to find potential collaborators in immunology who could help us translate this to a possible clinical endpoint.”

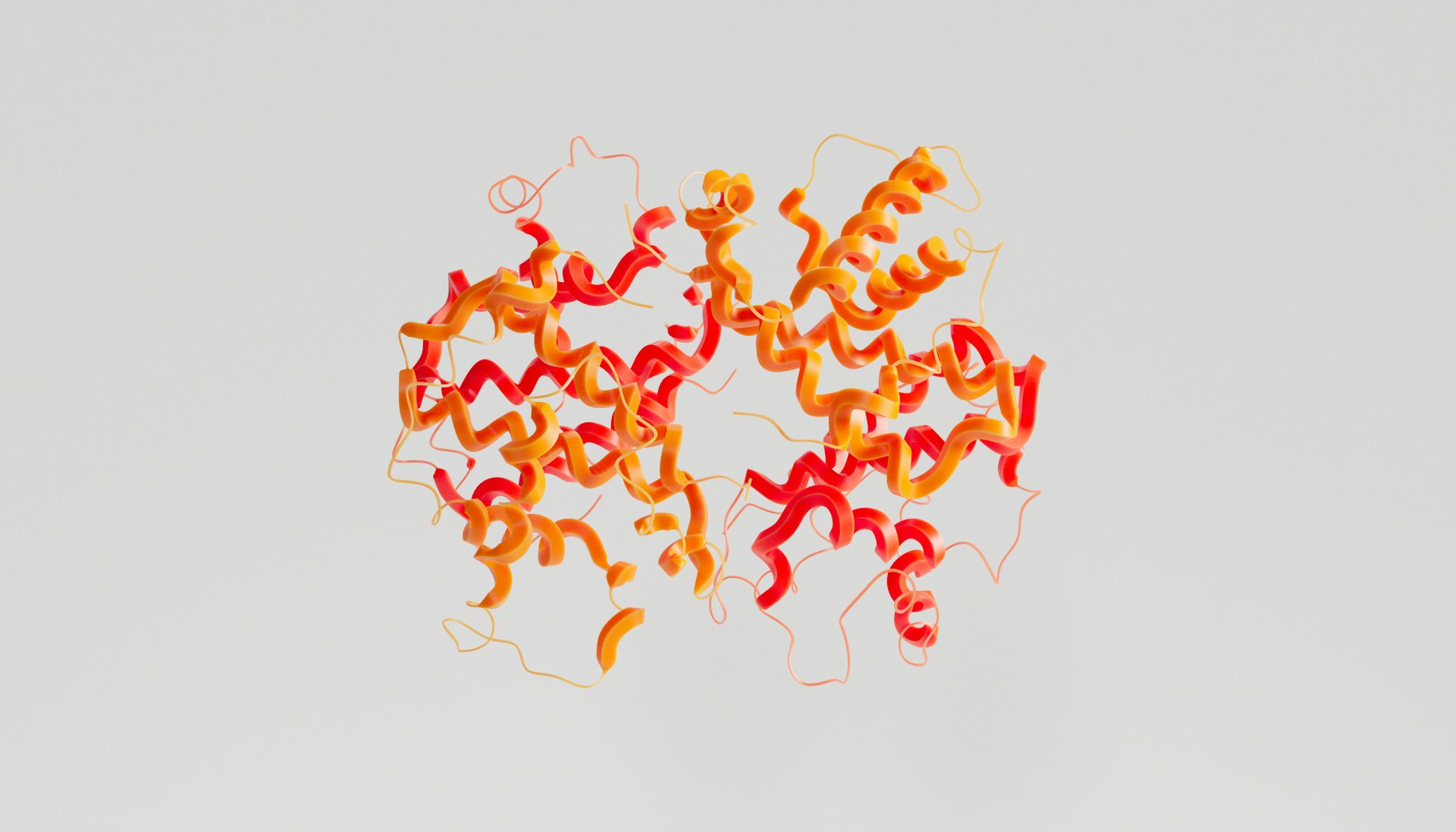

Scheidt’s group addressed the problem using total synthesis, a method in which a molecule is built step by step in the laboratory rather than extracted and inferred indirectly. Earlier analytical techniques, including advanced nuclear magnetic resonance, narrowed the possibilities down to two closely related structural models. The difference between them was subtle but critical: a mirror-image arrangement in a central region of the molecule. Such differences can determine whether a compound fits correctly into a biological target, much like the difference between left- and right-handed gloves.

By synthesizing both candidate structures from scratch and comparing them directly with samples derived from rye pollen, the team was able to confirm the correct configuration. A central challenge was recreating an unusually strained 10-membered ring that sits at the core of both secalosides. Rather than forcing this structure directly, the researchers built a larger and more flexible ring first, then induced a controlled transformation that snapped it into the correct smaller form. This strategy allowed them to overcome a bottleneck that had stalled progress for years.

With the structures now confirmed, attention can shift from identification to function. Knowing the exact geometry of secalosides A and B makes it possible to probe how they interact with immune cells and tumor environments. It also opens the door to rational modification, where chemists adjust specific features to improve stability, availability in the body, or selectivity toward certain biological pathways.

This work fits into a broader pattern in drug discovery, where natural products serve as starting points rather than finished medicines. Many widely used drugs trace their origins to compounds found in plants, microbes, or fungi, but few are administered in their original form. Instead, chemistry is used to refine these natural structures into versions that perform better under clinical conditions. Rye pollen compounds could follow a similar path, particularly given that extracts from rye pollen are already consumed as supplements for prostate health in some regions.

From an engineering perspective, the significance lies less in immediate clinical application and more in capability. The ability to reliably construct and modify complex natural molecules expands the design space available to researchers working at the interface of chemistry, biology, and medicine. It also provides a clearer platform for collaboration, allowing immunologists, pharmacologists, and chemical engineers to work from a shared and verified molecular framework.

While the current results do not constitute a cancer therapy, they resolve a foundational uncertainty that has limited the field for decades. By defining the structure of secalosides A and B, the Northwestern team has transformed an old biological observation into a problem that can now be addressed with modern tools. The next phase will determine whether these molecules, or engineered variants inspired by them, can be translated into practical strategies for cancer treatment or immune modulation.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).