A research group at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI), led by Professor Nima Rahbar, has developed a construction material that sets rapidly, can be recycled, and removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as it forms. The material, known as enzymatic structural material or ESM, is described in Matter and is attracting interest because it offers a route toward structural components that can be manufactured with far lower energy than traditional cement-based products.

Wang, S., Pourhaji, P., Vassallo, D., Heidarnezhad, S., Scarlata, S., & Rahbar, N. (2025). Durable, high-strength carbon-negative enzymatic structural materials via a capillary suspension technique. Matter, 102564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2025.102564

The work builds on the idea that biological systems routinely form minerals under mild conditions. The WPI team used an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of dissolved CO₂ into solid carbonate particles. These particles then bind together through a capillary suspension process, creating a rigid structure as the material cures. Reports from WPI and external science outlets note that the entire process takes hours rather than the days or weeks required for concrete, and it occurs at room temperature without the need for kilns or extended curing cycles.

Professor Nima Rahbar from Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) stated,

“If even a fraction of global construction shifts toward carbon-negative materials like ESM, the impact could be enormous”.

Concrete production remains one of the largest sources of industrial CO₂ emissions worldwide, so alternative binders have become a focus for both materials science and civil engineering research. In several interviews and institutional summaries, Rahbar emphasizes that ESM not only avoids the emissions associated with cement production but also actively stores CO₂. Producing one cubic meter of the material removes several kilograms of CO₂ from the atmosphere, a reversal of the carbon footprint typically associated with construction materials.

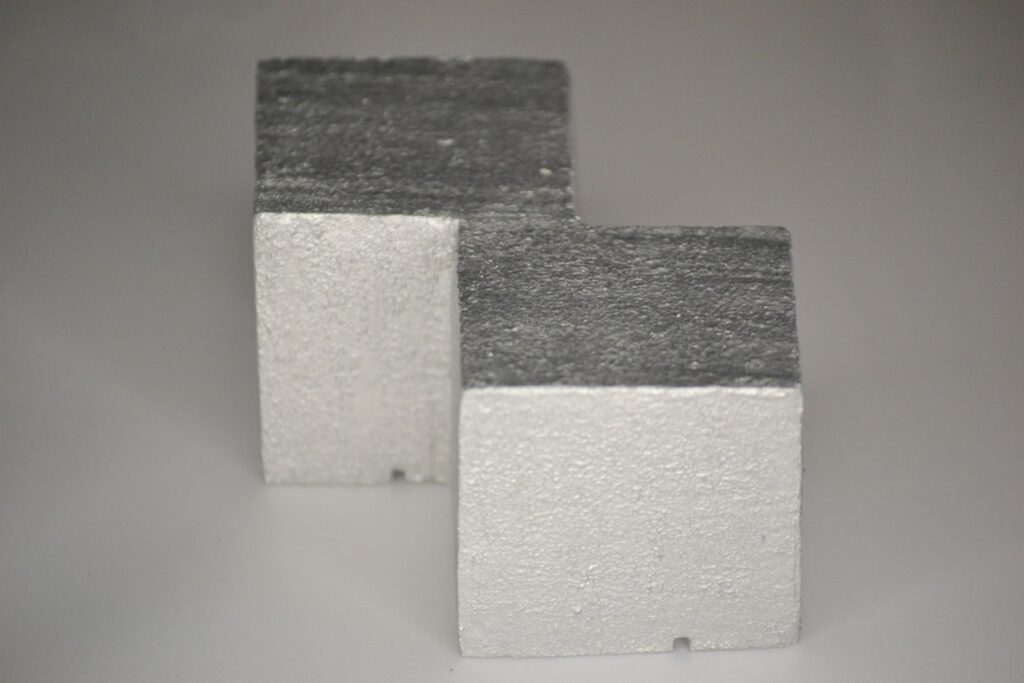

Researchers involved in the study, including Shuai Wang and colleagues, highlight that the mechanical performance of ESM can be tuned by adjusting particle size, enzyme distribution, and curing conditions. Early tests suggest that the material can reach strengths suitable for applications such as panels, pavers, and prefabricated components. Because it is formed through a low-temperature process, damaged parts can also be ground down and reused. This recyclability has been noted in several reports as a potential advantage for industries trying to reduce waste.

One of the practical benefits mentioned across multiple sources is the ability to produce structural elements quickly. For situations where construction speed is important, such as emergency shelters or temporary infrastructure, ESM’s short curing time may offer an operational benefit. The researchers also point out that traditional concrete derives its strength from hydration reactions that continue for weeks, while ESM reaches its final form much sooner, allowing earlier handling and installation.

The approach also raises questions about long-term durability and scalability, topics the team is continuing to study. The initial results show resistance to environmental degradation comparable to certain cement-based materials, but larger-scale production and field testing will be needed before industry adoption. Rahbar notes that the production method relies on widely available chemicals and enzymes, suggesting that manufacturing could be scaled without the need for specialized facilities.

As cities and construction firms look for ways to reduce emissions, materials that store carbon rather than release it may play a growing role. ESM is not intended as a direct replacement for all concrete applications, but the work provides an example of how bioinspired chemistry can contribute new options for structural materials. For sectors focused on modular building, prefabrication, and low-energy manufacturing, the technology offers a promising direction for further research and eventual deployment.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).