Professor Marc Porosoff and his team at the University of Rochester have reported a series of studies demonstrating that tungsten carbide, an abundant industrial material, can rival and in some cases outperform platinum in catalytic applications. Across publications in ACS Catalysis, the Journal of the American Chemical Society, and EES Catalysis, the researchers show that controlling the atomic phase of tungsten carbide enables efficient carbon dioxide conversion, plastic upcycling, and improved thermal management in tandem catalytic systems.

Perera, S. M. H. D., Harrington, B., Fadhul, A., Pickel, A. D., & Porosoff, M. D. (2026). Leveraging and understanding exotherms in tandem catalysts with in situ luminescence thermometry. EES Catalysis. https://doi.org/10.1039/D5EY00319A

Platinum has long served as a benchmark catalyst in fuel production, petrochemical processing, and environmental remediation. Its high activity and stability make it valuable in reactions involving hydrogenation, hydrocracking, and carbon dioxide reduction. However, platinum’s cost and limited global supply create economic and strategic constraints. Developing substitutes based on more abundant elements has been a central objective in catalysis research.

Professor Marc Porosoff and his team at the University of Rochester stated,

“We learned from this study that depending on the type of chemistry, the temperature measured with these bulk readings can be off by 10 to 100 degrees Celsius. That’s a really significant difference in catalytic studies where you’re trying to ensure that measurements are reproducible and that multiple reactions can be coupled.”

Tungsten carbide has been considered a candidate replacement for decades. It is widely used in cutting tools and wear-resistant coatings due to its hardness and chemical resilience. In catalysis, tungsten carbide exhibits electronic properties that resemble those of noble metals. Despite this similarity, inconsistent performance has limited its adoption in chemical manufacturing.

The Rochester team identified that the key challenge lies in phase control. Tungsten carbide does not exist as a single, uniform structure. Its atoms can organize into several crystalline phases, each with distinct surface chemistry. Conventional synthesis methods often produce mixtures of these phases, making it difficult to correlate structure with catalytic activity.

To address this issue, doctoral researcher Sinhara Perera and colleagues developed a method to engineer tungsten carbide directly inside a high-temperature reactor using temperature-programmed carburization. By adjusting reaction conditions above 700 degrees Celsius, the team synthesized catalysts enriched in specific phases. This in situ approach allowed them to evaluate performance under realistic operating conditions rather than relying solely on ex situ characterization.

Their work identified the β-W2C phase as particularly active for reactions that convert carbon dioxide into fuel precursors and other industrial intermediates. While thermodynamically stable phases dominate under equilibrium conditions, the study shows that kinetically controlled phases can offer superior catalytic performance. This finding highlights the importance of non-equilibrium synthesis strategies in materials design.

In parallel, the researchers explored tungsten carbide’s potential in plastic waste conversion. In collaboration with Linxiao Chen at the University of North Texas and Siddharth Deshpande at the University of Rochester, the team investigated hydrocracking of polypropylene, a common plastic used in packaging and consumer goods.

Hydrocracking breaks long polymer chains into shorter hydrocarbons that can be reused as chemical feedstocks. Platinum-based catalysts are widely used in petroleum refining for this purpose, but adapting them to plastic waste streams has proven difficult. Many conventional catalysts rely on microporous supports that restrict access for large polymer molecules. Contaminants in mixed plastic waste can also deactivate noble metal catalysts.

The study demonstrated that phase-controlled tungsten carbide functions as an intrinsically bifunctional catalyst, combining metallic and acidic characteristics in a single material. This dual functionality enables efficient cleavage of carbon–carbon bonds without requiring complex support structures. The team reported that tungsten carbide achieved more than tenfold improvements in catalytic efficiency compared with conventional platinum systems under similar conditions.

The cost difference between tungsten carbide and platinum further strengthens its appeal. Tungsten is far more abundant in the Earth’s crust, and carbide synthesis does not depend on rare precious metals. If scaled effectively, this approach could lower the material cost of catalytic processes used in recycling and fuel production.

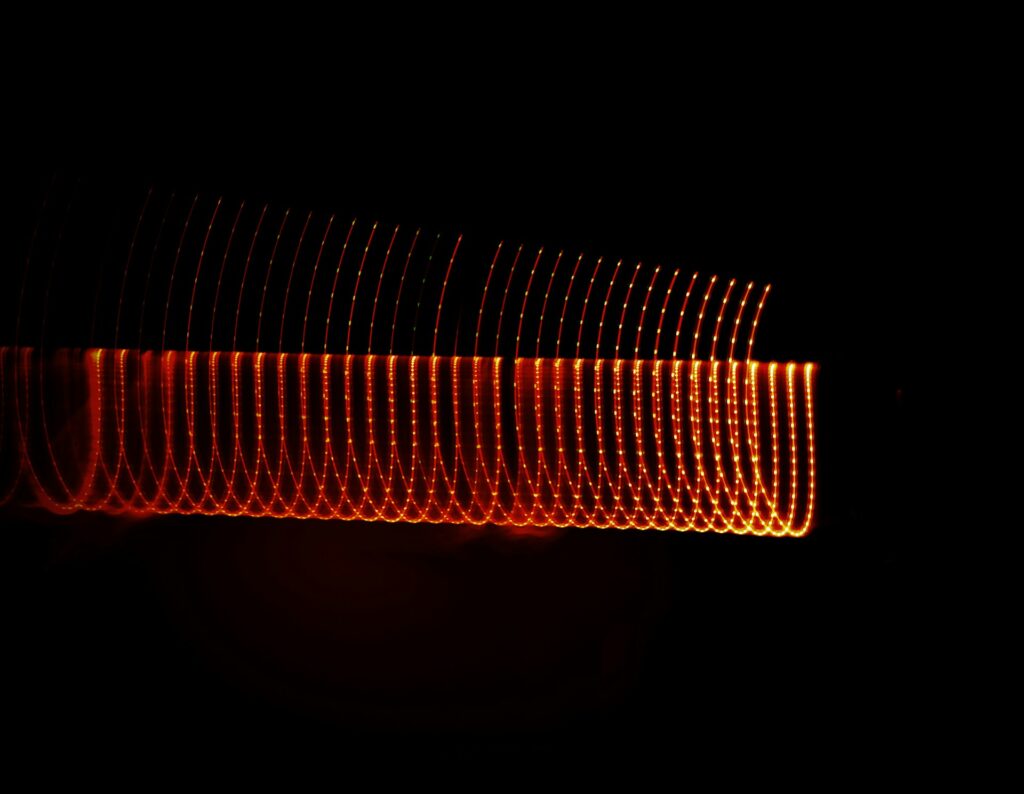

Accurate temperature measurement emerged as another critical factor in optimizing catalytic systems. Chemical reactions often involve simultaneous exothermic and endothermic steps. Surface temperatures at active sites can differ significantly from bulk reactor readings. In collaboration with Andrea Pickel’s group in mechanical engineering, the Rochester team implemented in situ luminescence thermometry to measure catalyst surface temperatures directly.

The researchers found discrepancies of up to 100 degrees Celsius between bulk and surface measurements. Such differences can influence reaction pathways, product selectivity, and catalyst stability. By improving temperature diagnostics, the team demonstrated more precise coupling of tandem reactions in which heat released by one step drives another.

Collectively, these studies illustrate a broader shift in catalyst development. Rather than relying solely on scarce noble metals, researchers are revisiting abundant materials and refining their atomic structure to unlock performance. The emphasis on phase control, in situ characterization, and thermal precision reflects an integrated engineering approach.

Tungsten carbide’s promise extends beyond the specific reactions examined. Its electronic similarity to platinum suggests potential in hydrogen evolution, carbon monoxide conversion, and other electrochemical processes. Continued optimization of synthesis methods and reactor design will determine how broadly it can be applied.

For sustainable chemical manufacturing, replacing platinum with abundant alternatives addresses both economic and environmental concerns. Lower catalyst costs can accelerate deployment of carbon recycling technologies and plastic upcycling systems. Improved measurement tools, meanwhile, enhance reproducibility and scalability.

The Rochester findings demonstrate that widely available materials may hold untapped catalytic capabilities when their atomic structure is carefully engineered. As research progresses, tungsten carbide may transition from an industrial hard material to a central component in sustainable chemistry and energy systems.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).