Michael Shatruk and colleagues at Florida State University are rethinking how new magnetic materials can be created by design rather than discovery. In a recent study published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, the research team reports the synthesis of a new crystalline material whose magnetic behavior emerges from competition at a chemical boundary. By intentionally combining closely related compounds with incompatible crystal structures, the group demonstrated a controlled route to generating complex magnetic order that does not exist in either material on its own.

Magnetism in solids originates from atomic spin, a quantum property that gives each atom a small magnetic moment. In conventional magnetic materials, these moments align in relatively simple patterns, producing ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic behavior. Such ordering underpins most everyday magnetic technologies, from electric motors to data storage. More intricate arrangements of spins are possible, but they are uncommon and often difficult to stabilize under practical conditions.

Michael Shatruk from Florida State University stated,

“We thought that maybe this structural frustration would translate into magnetic frustration. If the structures are in competition, maybe that will cause the spins to twist. Let’s find some structures that are chemically very close but have different symmetries.”

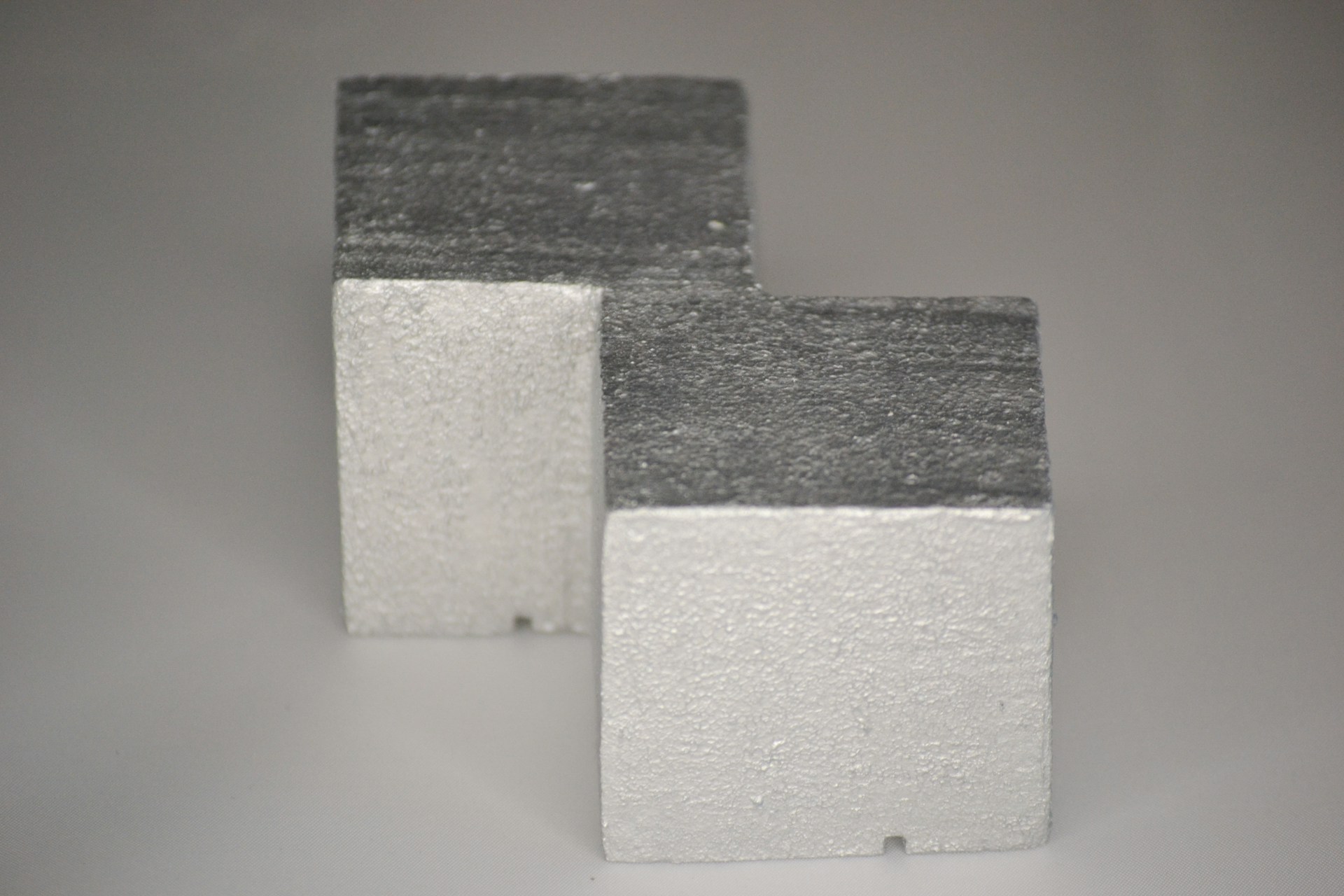

The Florida State University team focused on a chemical design strategy that introduces structural competition into a material system. They combined two intermetallic compounds with nearly identical chemical compositions but different crystal symmetries. One compound contained manganese, cobalt, and germanium, while the other substituted germanium with arsenic, an element adjacent to it in the periodic table. Although chemically similar, the two compounds favor distinct lattice structures, creating instability when brought together.

When the mixed system was allowed to crystallize, neither of the original structures fully prevailed. Instead, the material adopted a new structure that reflects this structural frustration. The researchers proposed that this instability at the lattice level would extend to the magnetic interactions between atoms. Their measurements confirmed that the atomic spins do not align in straight or alternating patterns but instead form repeating, cycloidal arrangements that resemble skyrmion-like spin textures.

To resolve this magnetic structure, the team used single-crystal neutron diffraction, a technique well suited for studying magnetism at the atomic scale. Experiments were carried out using the TOPAZ instrument at the Spallation Neutron Source at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Advances in data analysis and modeling allowed the researchers to determine the complex spin arrangement with a level of certainty that was not possible only a few years ago.

These twisted spin textures are of interest because they can be manipulated using relatively small amounts of energy and are less sensitive to certain defects in the material. From an engineering standpoint, this raises the possibility of magnetic devices that operate with lower power consumption and greater stability. In data storage technologies, such spin structures could enable higher information density, while in large computing systems they could contribute to reduced energy and cooling demands.

The implications also extend to quantum technologies. Magnetic states that are robust against noise and imperfections are considered promising building blocks for fault tolerant quantum computing. While the present work is focused on fundamental materials science, it helps clarify the conditions under which such states can be deliberately created and controlled.

Rather than searching existing materials for rare magnetic behavior, this study illustrates a predictive approach rooted in chemistry and crystallography. By understanding how small changes in composition influence structural and magnetic competition, researchers can expand the range of materials available for future technologies. The ability to work with more accessible elements and simpler synthesis routes also improves the feasibility of scaling these materials beyond the laboratory.

This work suggests that structural frustration can serve as a practical design principle for magnetic materials. As experimental techniques and computational tools continue to mature, approaches like this may allow engineers and scientists to tailor magnetic properties with greater precision, linking atomic scale design directly to functional performance in next generation devices.

Adrian graduated with a Masters Degree (1st Class Honours) in Chemical Engineering from Chester University along with Harris. His master’s research aimed to develop a standardadised clean water oxygenation transfer procedure to test bubble diffusers that are currently used in the wastewater industry commercial market. He has also undergone placments in both US and China primarely focused within the R&D department and is an associate member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE).